-

The 2022 Ferragosto Picnic: Fun, Food and Friendship

By Maria Andrea-Yothers

AMHS members, family and friends enjoyed fun and fellowship at the 2022 Ferragosto Picnic.

Credit: Sam YothersFerragosto 2022 was celebrated on Sunday, August 14, back at Fort Ward Park in Alexandria, Virginia, from 3:00 – 7:00 PM. Approximately forty AMHS members, friends and family came together to celebrate with a wonderful picnic.

We were treated to some delicious food prepared by some skillful cooks. Edvige D’Andrea’s sausage and peppers were a personal favorite among an abundant variety of Italian foods which were shared. There were also delicious pasta salads, cheeses, Italian salami, olives, and homemade biscotti. This year, we were treated to grilled arrosticini and caciocavallo cheese, courtesy of AMHS member Willy Meaux, who graciously grilled 100 arrostocini skewers. They, and the cheese, were quite the hit. No picnic celebrating Italia and its traditions would be complete without vino. We enjoyed plenty of red, white and rose. Many thanks to Sam Yothers for also making sure there was “birra Italiana” for those who preferred a cold beer or two on a hot day, and to Lucio D’Andrea who brought his ever-popular homemade limoncello.

Attendees enjoyed games of Italian cards, bocce, and cornhole toss (courtesy of AMHS Board member John Dunkle). We also welcomed two new members, Michael Iademarco and Natalie Duncan.

Many thanks to all of you who attended! Also, a special “grazie” for those who helped with set-up and tear-down. Fort Ward Park proved once again to be a perfect venue. Taking time to laugh and celebrate together was truly a wonderful and memorable event.

September/October 2022

-

A Message from the President

Dear members and friends:

I hope that everyone has had an enjoyable and relaxing summer and that you are ready to welcome the fall season.

We did not have any general meetings over the summer, but we were hardly inactive. On July 31, we held a virtual event in which Daniel Piazza, the Chief Curator of the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, gave a very informative presentation entitled “The Fascist Style in Italian Philately, 1922-1941”. This period in Italian stamp history was unique for a number of reasons and Mr. Piazza clearly laid them out in his excellent lecture and accompanying slides.

On August 14th, we held our annual Ferragosto picnic at Fort Ward Park in Alexandria, Virginia. The weather was nearly perfect for a picnic – low eighties with some cloud cover to block out the sun. There was some light rain around 6 PM, but fortunately it came at the tail end of the day. AMHS family members and friends spent a relaxing afternoon enjoying good food, including arrosticini and caciocavallo, good drink, good fun and good company.

Then, on August 27th, we presented another virtual program. Our guest speaker was Edvige Giunta, Professor of English at Jersey City University, who discussed the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of New York City. This tragic event of 1911 killed 146 female workers, many of whom were young Italian immigrants, and the subsequent outcry helped spur a movement for workers’ right and unions. The talk was excellent and covered a piece of history that is too often overlooked by the general public and, unfortunately, even by Italian Americans.

Looking ahead on the calendar, AMHS will host a Happy Hour at Il Bocca al Lupo restaurant/bar on September 14 at 5:30 PM. Il Bocca al Lupo is a soccer-themed, Roman-style venue located at 2400 Wisconsin Avenue in northwest Washington, D. C. The food is authentically Italian and the environment is congenial. Check out our website for additional details on the get-together.

Our next in person general meeting will take place on September 18 at 1 PM in the Casa Italiana Sociocultural Center. Our guest speaker will be Eric Denker, the Senior Lecturer at the National Gallery of Art and a longtime fan of Venice. Eric will give us a talk on this unique city and his presentations are so good that listening to his talk on the 18th may very well be the next best thing to actually being in Venice. Mark the date on your calendar!

Stay tuned for the grand opening of the AMHS online shop. It will feature many products available for purchase with the AMHS logo on them. The shop will greatly expand the number of products for sale and will make purchase and payment much easier and more efficient than in the past. We’ll let you know when it goes live.

Have you ever thought about serving a term on the AMHS Board of Directors? We have two openings now for three-year terms that begin on January 1, 2023. The Board meets six times a year, and all the meetings are virtual. So even if you don’t live in the Washington, D.C. area, you can still lend your expertise to the Society and help to shape its future direction. If you’re interested, please contact Maria D’Andrea-Yothers (uva051985@comcast.net). Fresh ideas and different backgrounds will help to keep our organization strong.

Thanks for reading and have a pleasant fall season.

Best regards,

Ray LaVerghetta

September/October 2022

-

Washington Area Vespisti Take Trip of a Lifetime to Italy

By Nancy DeSanti

Members of the D.C. and Sulmona Vespa Clubs celebrate their ride together.

Credit: Courtesy of Willy Meaux

This summer, nine Vespisti of the Vespa Committee of Washington, D.C., led by AMHS member Willy Meaux, set off on an epic two-week Vespa ride from Rome to a first Vespa rally in Sulmona in the province of L’Aquila in Abruzzo.

The trip, which began June 30, 2022, then took the riders through Umbria to Spoleto and Perugia, on to Tuscany via Montalcino, Siena and Florence. Then the riders went to the Liguria area to Lerici, the Golfo dei Poeti and the first borgo of the Cinque Terre, and Carrara, followed by a second Vespa rally in Sarzana. The final stop of the journey was to Pontedera, to see the Museo Piaggio which presents the history of the Vespa from its beginning in 1946 to today.

The highlights of the trip were the incredible Raduno of the Vespa Club of Sulmona including a beautiful ride to Scanno, a city with a great lake high in the mountains, and Pacentro, a historic city with a castle and fantastic views of the Peligna Valley. Next up was an incredible ride through Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo with a very challenging but thrilling route filled with hours of 180 degree turns down steep, narrow roads along the cliffs of the highest peaks of the Apennine Mountains.

The riders then enjoyed the beautiful cities of Spoletto, and Perugia, a monastery stay in Pienza, two incredible days in Florence hosted by the Vespa Club of Florence, the beautiful port areas of Lerici, Sarzana and the Golfo dei Poeti, and a taste of Cinque Terre. Then it was on to the marble caves of Carrara, the Piaggio Museum in Pontedera, a night in the Castello Fosdinovo, and a beautiful evening again on the Mediterranean in Orbetello before returning to Rome. It all added up to 2,000 kilometers on the Vespas and the most wonderful gastronomic experiences along the way.

AMHS members may recall that Willy was our speaker at the Vespa Raduno at Casa Italiana on September 22, 2019. The event honored the Abruzzese inventor of the Vespa, Corradino D’Ascanio. The president of the Sulmona Vespa Club, Panfilo D’Angelo, was our special guest. (The Sulmona Vespa Club is a chapter of the Vespa Club of Italy).

The vespa was a symbol of the rebirth of Italy following liberation by the Allies.

Credit: Archival photo, NARAGiving a little background on the Vespa (“wasp” in Italian), Willy noted that while slower than a car, a Vespa could easily navigate Italy’s ancient and narrow roadways. Introduced to the world in 1946 as Italy was emerging from World War II in ruins, it was inexpensive to own and operate, and its commercial success led to its iconic status as a symbol of Italian culture, design, style and la dolce vita. Whipping through the streets on this simple, elegant and robust piece of automotive engineering gave riders a sense of freedom. Like all Italian inventions, it was conceived with aesthetics in mind.

Willy noted that the Vespa Committee of Washington, DC Inc., of which he is a past president, has founded a new adventure travel program called “The Vespa Bridge to Italy.”

He said this summer adventure was truly a bucket list trip, and a documentary movie of the entire adventure is now in production, to be released in 2023. Proceeds from the Vespa Committee’s film will go to support future opportunities for film students to go to Italy to create films about that country, its rich culture and these Vespa journeys. Willy said the Vespa Committee is very proud to have supported three collegiate film students in this first film project. Says Willy: “Get ready to binge when the film is released as we will also include the incredible Italian cuisine we discovered along the journey that was unique to each region.”

Stay tuned for news about the upcoming documentary as well for news about The Vespa Bridge to Italy 2023. You can learn more about the foundation at www.vespacommittee.org.

From its humble beginnings, the vespa became an icon of La Dolce Vita.

Credit: Instagram @officialmadalinagheneaSeptember/October 2022

-

Dan Piazza Speaks on History of Italian Stamps Under Fascism

By Nancy De Santi

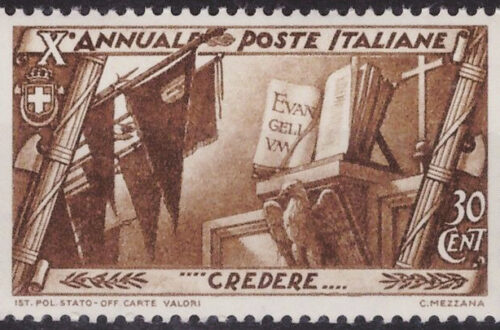

An Italian stamp from 1932 blending fascist and religious symbolism.

Credit: Image provided by Dan Piazza

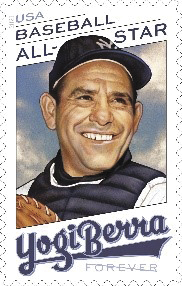

AMHS members were treated to a very interesting and informative virtual talk on July 31, 2022, by distinguished guest speaker Daniel A. Piazza, who discussed an important historical period of Italian stamps, namely the Fascist era from 1922 to 1941.

Dan has been the Chief Curator of the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum since 2014. He is responsible for exhibitions, acquisitions and research related to the museum’s collection of six million postage stamps and postal artifacts comprising one of the largest such collections in the world.

As Chief Curator, his exhibitions have included “Freedom Just Around the Corner: Black America from Civil War to Civil Rights,” which won the 2016 Smithsonian Research Prize. A few of his other exhibitions were on Alexander Hamilton, on 100 years of the national parks, and on the world’s most famous stamp (in case you’re wondering, it’s the British Guiana One-Cent Magenta).

Dan earned his Masters in American history from Syracuse University, where he also taught history courses and was a Fellow in the university library’s rare book collection. He lectures widely and contributes to many philatelic journals and collector periodicals. He is also a member of several national and international philatelic societies including the prestigious Royal Philatelic Society of London.

Dan told us that his father’s side of the family is from Agrigento, Sicily, and his mother’s side of the family has roots in Catanzaro (Calabria), Genoa and Friuli.

One of the interesting things we learned from Dan is that despite its name, over half of the material in the National Postal Museum is international. The museum opened to the public in 1993.

Dan also talked about the most famous Italian stamp artist Corrado Mezzana, who designed stamps for the Fascists and the Vatican at the same time. Dan explained that great stamp artists such as Mezzana have a knack for combining pictures and text in a very small space, and so their services are much in demand. He noted that one of Mezzana’s last sets was Italia al Lavoro in 1950, featuring traditional crafts of all 20 regions of Italy.

The first Fascist stamps were issued within a year of Benito Mussolini’s March on Rome in October 1922, and Dan said you can trace the development of the propaganda beginning with the Fiume D’Italia stamps, including a stamp of the controversial Abruzzese poet Gabriele D’Annunzio. Dan noted that the sale of these stamps basically funded their operations.

The consistent themes of the Fascist stamps were pioneered with the Fiume stamps, he noted, including the use of allegorical or historical imagery, and the use of Latin inscriptions. These were not features of Italian stamps prior to the Fascist era, he explained.

The Fascist stamps that debuted in 1923 featured a blending of futurism, art deco and the styles of the 1920s and 1930s. Dan said one of the stamps which added on a cost above the normal price was sometimes referred to as the “Blackshirt pension plan.”

In 1932 on the 10th anniversary of the March on Rome, Mezzana designed stamps very important to the Fascist regime having the theme of Romanità, meaning the political and cultural concepts and practices by which the Romans defined themselves.

Mezzana wasn’t a fascist, Dan explained, but rather he worked on stamp contracts and he used his talents to design Vatican stamps as well.

The stamps of the period also depicted the transatlantic liner Rex which brought many immigrants to America, and Dan noted that Mussolini referred to Italian-American communities in America and Argentina as “colonies.”

Interestingly, Dan explained that Mussolini seldom appeared on stamps, unlike Hitler and Franco, because it might not have been popular with the Italian public and he still had to deal with King Victor Emanuel III. Over time, however, the stamps became more militaristic, and aircraft were often depicted.

Dan noted that the Fascists did have religious stamps to placate the population, although Mussolini himself was not religious. For the first time, there was a stamp depicting Jesus, but as Dan explained, it was seen as a “smokescreen” masking hostility to religion.

In 1941, Hitler and Mussolini appeared on a stamp together. The Fratellanza d’armi italo-tedesca stamp even featured a Nazi swastika.

Stamps were also issued for Italian East Africa (Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritreaa). The basic idea of the Fascist stamps was two-fold — as propaganda and as a way to get money from collectors.

Dan noted that there is no Italian philatelic society in the United States, and he speculated that it was probably because of the past connection to Fascism. In Italy in 2019, there was an attempt to ban Fascist imagery, including stamps, but this was not enacted. He noted that there is a lot of interest in philately in Italy and there are many active philatelic societies. He was asked about the possibility of a U.S. stamp honoring Constantino Brumidi, often called the “Michelangelo of the Capitol” who was awarded a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal in large part through the efforts of our late AMHS member Joe Grano. Dan suggested organizing a group effort to write to the Citizen’s Stamp Advisory Committee at their website, since the committee makes recommendations to the Postmaster General on stamp subjects.

September/October 2022

-

Italian Labor Leaders Advanced Social Justice

(Editor’s Note — Many Italian immigrants were prominent in the formation and advancement of the labor movement in the United States. To commemorate Labor Day, AMHS Board Member Joseph “Sonny” Scafetta, Jr. profiles three such activists who hailed from our regions in Italy and fought for social justice for working people.)

Carlo Tresca

Credit: wikipedia

Carlo Tresca

Carlo Tresca was born in the town of Sulmona (population 24,221 in the 2017 Census) in the province of L’Aquila in Abruzzo on March 9, 1879. After graduation from high school and a year in the seminary, he went to work for four years as a secretary for the Italian Federation of Railroad Workers. He also became the editor of Il Germe (The Germ), a socialist weekly newspaper based in Sulmona. In 1904 when he was 25, Tresca was convicted of libel based on his report about the torture of prisoners in the local jail. To evade prison, he immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City. His wife and young daughter soon joined him there.

Also in 1904, Tresca was elected Secretary of the Italian Socialist Federation of North America (ISFNA) and became editor of Il Proletario (The Proletarian). In 1907, he resigned as editor and began publishing his own newspaper, La Plebe (The Plebian). He soon moved his newspaper to Pittsburgh where he espoused socialist ideals to Italian-American miners and mill workers. In 1909, he closed his newspaper in Pittsburgh, became a U.S. citizen, and started another newspaper, L’Avvenire (The Future), back in New York City.

In 1912, Tresca quit the ISFNA and joined the Industrial Workers of the World. He became involved in various strikes, first by textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912, again by textile workers in Little Falls, New York, also in 1912, then by hotel workers in New York City in 1913, by silk mill workers in Paterson, New Jersey, also in 1913, by miners in Colorado in 1914, and again by miners in the Mesabi Range of Minnesota in 1916. In Minnesota, Tresca was arrested for murder and jailed for nine months but was eventually released without going to trial for lack of evidence tying him to the crime.

With the entry of the United States into World War I in April 1917, his newspaper was suppressed under the Espionage Act. Tresca then became a frequent speaker at anti-war rallies. After the war ended in November 1918, he started another newspaper, Il Martello (The Hammer). When the American Civil Liberties Union was formed in early 1920, he became a member. In August 1920, he organized a successful picket of British ships by dock workers to protest the arrest of an Irish doctor after Ireland had gained its independence from Great Britain.

During this incident, Tresca met an Irish-American political activist, Binna Martin, with whom he began an affair. When his wife learned about the affair, she left him and took their daughter with her but did not divorce him. Tresca and Martin had a son, Peter Martin, who was born in early 1923.

After the birth of his son, Tresca allowed an advertisement for a birth control pamphlet to be printed in his newspaper. As a result, he was arrested in August 1923 and found guilty of publishing pornography after a trial two months later. The verdict was affirmed on appeal on November 10, 1924. Tresca entered the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, on January 5, 1925, to serve his sentence of one year and one day. He was released on January 6, 1926.

Tresca returned to his newspaper to publicize and raise funds for the appeal of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti of their death sentence for the murder of two men in Massachusetts. He continued his efforts until Sacco and Vanzetti were executed on August 23, 1927. Tresca then turned the attention of his newspaper to making anti-fascist attacks against Benito Mussolini in Italy and anti-communist attacks against Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union. When the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936, Tresca supported the republic against the fascist forces of General Francisco Franco.

Mourners at Carlo Tresca’s funeral in Manhattan in 1943.

Credit: By Marjory Collins from Library of Congress: Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph CollectionIn 1937, Tresca was appointed by the governor of New York to be a member of the Dewey Commission which cleared Leon Trotsky of all charges made during his sham trial in Moscow. In early 1938, Tresca as editor accused the Soviets of kidnapping Juliet Stuart Poyntz to prevent her defection from the Communist Party USA because, before she disappeared, she had talked to him about “exposing the communist movement”.

After communism was discredited in the United States when Stalin signed a nonaggression pact with Nazi Germany under Adolph Hitler in August 1939, Tresca began to direct his editorial attacks against the Mafia in New York City. The withering fire of his critical public campaign drew the attention of law enforcement to focus on the Mafia. On January 11, 1943, Tresca was near his newspaper office crossing Fifth Avenue at 15th Street on foot when a black Ford pulled up beside him. A short, squat man in a brown coat jumped out and shot Tresca with a hand gun in the back of the head, killing him instantly. He was two months shy of his 64th birthday. An investigation later determined that Tresca was killed by a parolee, Carmine Galante, on the order of Frank Garofalo, under boss to Joseph Bonanno, who headed a New York crime family. No charges were ever brought because of insufficient evidence.

Sources, all accessed July 25, 2021:

- Salvatore J. LaGumina et al., The Italian-American Experience: An Encyclopedia at pgs. 640-641 (Garland Publishing, Inc. 2000)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlo_Tresca

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulmona

Virgilia D’Andrea

Credit: commons.wikimedia.orgVirgilia D’Andrea

Virgilia D’Andrea was born in Sulmona (population 24,221 in the 2017 Census) in the province of L’Aquila in Abruzzo on February 11, 1888. Both her parents died when she was six, so her relatives enrolled Virgilia in a Catholic boarding school in the town. During her education, she read hundreds of books, developing an affinity for poetry. She remained in the boarding school until she was 18 when she qualified as a teacher. She taught in different elementary schools in Abruzzo for the next ten years.

In 1917 at the age of 29, she met an anarchist journalist named Armando Borghi at a meeting of a radical trade union which he headed. He was six years her senior. They became companions, then lived together. Although a free love advocate, D’Andrea maintained a monogamous commitment to Borghi throughout her life. During that same year, she left teaching to join the protest movement against Italian participation in World War I. The couple was subjected to house arrest and legally confined until the war ended in November 1918.

Between 1918 and 1922, she gave talks and published a number of poems in Avanti! which was the newspaper of the Socialist Party in Rome. In 1922, she published her first book entitled Tormento which was a collection of 19 poems written in rhyme. Her poems reflected the tension of social protest prevalent after the war and expressed her angst in the wake of political defeats dealt the workers’ movement. The book was well received and a total of 8,000 copies were sold.

After Mussolini’s March on Rome in October 1922, D’Andrea and Borghi started to receive death threats, so they decided to emigrate from Italy. They first went to Berlin, Germany, in 1923, then to the Netherlands in 1924, and finally to France in 1925. While living in Paris, D’Andrea published her second book entitled L’Ora di Marmaldo (The Hour of Marmald) which was a volume of poetic prose attacking fascism.

In the Fall of 1928, D’Andrea and Borghi immigrated to the United States and settled in Brooklyn, New York. In 1929, a second edition of Tormento was published in Italy. It was immediately seized by the fascist government of Mussolini who charged that it inspired revolt because it “excited the spirits”. Citing her advocacy of free love, the government then charged D’Andrea in absentia with “reprehensible moral behavior”.

During the next four years, she gave speeches and conducted lecture tours across the United States to help rejuvenate Italian-American labor groups. In doing so, she connected emotionally with her working-class audiences. However, she developed breast cancer and died in New York City on May 12, 1933, three months after her 45th birthday. Borghi was at her side when she died.

Before the year was over, Borghi had her collection of unpublished writings, including poetry, prose, and autobiographical memories, printed in her third and last book entitled Torce Nella Notte (Torches in the Night). It was her most successful work. In 1946 after World War II ended, Borghi returned to Italy where he lived unmarried for the rest of his life.

Sources, all accessed July 21, 2021:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virgilia_D’Andrea

- https://www.katesharpleylibrary.net/8sf86b

- https://attackthesystem.com/2021/05/29/betrayal-vengeance-and-the-anarchist-ideal

- https://libcom.org/history/borghi-armando-1882-1968

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulmona

Arturo Giovannitti

Credit: wikipediaArturo Giovannitti

Arturo Giovannitti was born on January 7, 1884, in Ripabottoni (population 4,937 in the 1881 Census) in the province of Campobasso in Molise. He was the oldest of three sons born to Domenico Giovannitti, a pharmacist, and his wife, Adelaide Levante. After he finished high school, he immigrated in 1901 to Canada to study in a Presbyterian seminary where he learned English and French. He then transferred to McGill University in Montreal to complete his courses in theology.

In 1905, he came to New York City to study further at the Union Theological Seminary and briefly at Columbia University, but he did not graduate. Due to a lack of funds, he quit his studies and started to assist rescue missions for Italians in Brooklyn where he was appalled by the poor conditions of the immigrants. Determined to assist them, he gave up his quest for the ministry and started working in 1907 with Carlo Tresca on La Plebe (The Plebian), a socialist journal. In 1908, he joined the Italian Socialist Federation of North America. His first workers’ poem was published in the May Day issue of Il Proletario (The Proletarian) which was the Italian newspaper of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). In 1911, he became the editor of the newspaper.

On January 1, 1912, in accordance with a new state law, the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, posted new rules limiting the hours of workers to 54 per week, down from 56. When employers did not adjust wages up to compensate for the two lost hours, a strike occurred. On January 12, the IWW Local 20 called for Joseph Ettor (born Giuseppe Ettore) to come to the city to lead the strike. Ettor then called Giovannitti to come to help with relief efforts. Upon his arrival, Giovannitti gave his most famous address, The Sermon on the Commons, which modified Jesus’s Beatitudes to more aggressive stances. On January 29, a 16-year-old picketing striker named Anna LoPizzo was shot and killed during a police crackdown on an unruly crowd of workers. An Italian, Joseph Caruso, was arrested and jailed for murder. Although Ettor and Giovannitti were three miles away, they were arrested and jailed for inciting a riot. While in jail, Giovannitti wrote many poems. The most famous was The Walker inspired by the footsteps of a prisoner pacing in a cell above him at night. The trial began in Salem on September 30, 1912, eight months after their arrests. There were 19 defense witnesses who testified that the shooter was a policeman, not Caruso. Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered their own closing statements at the end of the almost two-month trial. Giovannitti’s speech brought many in the gallery to tears. After three days of deliberations, the jury acquitted all three defendants on November 26, 1912.

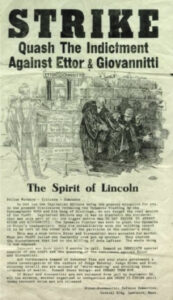

A flyer demanding the release of Giovannitti and Ettor.

Credit: Italy HeritageThe trial had been followed closely by the press throughout North America and Europe. As a result of his newfound fame, Giovannitti returned to his work as an editor, became a U.S. citizen, avoided involvement in strikes, and published his first book of poems, Arrows in the Gale, in early 1914. In reaction to the start of World War I later that year, he wrote an anti-war play called As It Was in the Beginning which had a short Broadway run in 1917. After the war was over at the end of 1918, his mother wrote to him to tell him that both his brothers had been killed in battle. This tragic news depressed him so much that he began to drink heavily. Nevertheless, between bouts of depression and drinking, he began to travel around the United States urging workers to join the IWW because it was an amalgamated union of all races and nationalities.

After Benito Mussolini seized power, Giovannitti helped to organize the Anti-Fascist Alliance of North America in 1923 and was elected Secretary. He then married Carrie and had three children who they named Roma, Vera, and Lenin. He traveled for years to speak before Italian-American workers about the dangers of fascism. When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, he sharpened his focus on his anti-fascist activities. In 1943, he gave the eulogy at the funeral of his friend, Carlo Tresca, who had been shot by a mafioso in New York.

In 1950 at the age of 66, Giovannitti was stricken by neuropathy, a vitamin B deficiency, not fully understood at that time, which resulted in the paralysis of both of his legs below the knees. Consequently, he returned to writing and published a collection of his Italian poems in a book entitled Quando Canta il Gallo (When the Rooster Sings) in 1957. He was editing a collection of his English poems when he died in the Bronx on January 31, 1959, about three weeks after his 75th birthday. These English poems were published posthumously as The Collected Poems of Arturo Giovannitti in Chicago by Clemente & Sons in 1962.

Sources (all accessed December 12, 2021):

- Salvatore J. LaGumina et al., The Italian-American Experience: An Encyclopedia, at p. 268 (Garland Publishing, Inc. 2000)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arturo_Giovannitti

- https://www.italyheritage.com/great-italians/history/giovannitti-arturo.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ripabottoni

September/October 2022