Three Gentlemen from Venafro

By Joseph “Sonny” Scafetta, Jr.

(Editor’s Note: Continuing our series of articles by Sonny Scafetta about notable individuals from Abruzzo and Molise, we feature three men from the city of Venafro, which happens to be the birthplace of my paternal grandfather. We hope you enjoy reading about these historical figures. – Carmine James Spellane)

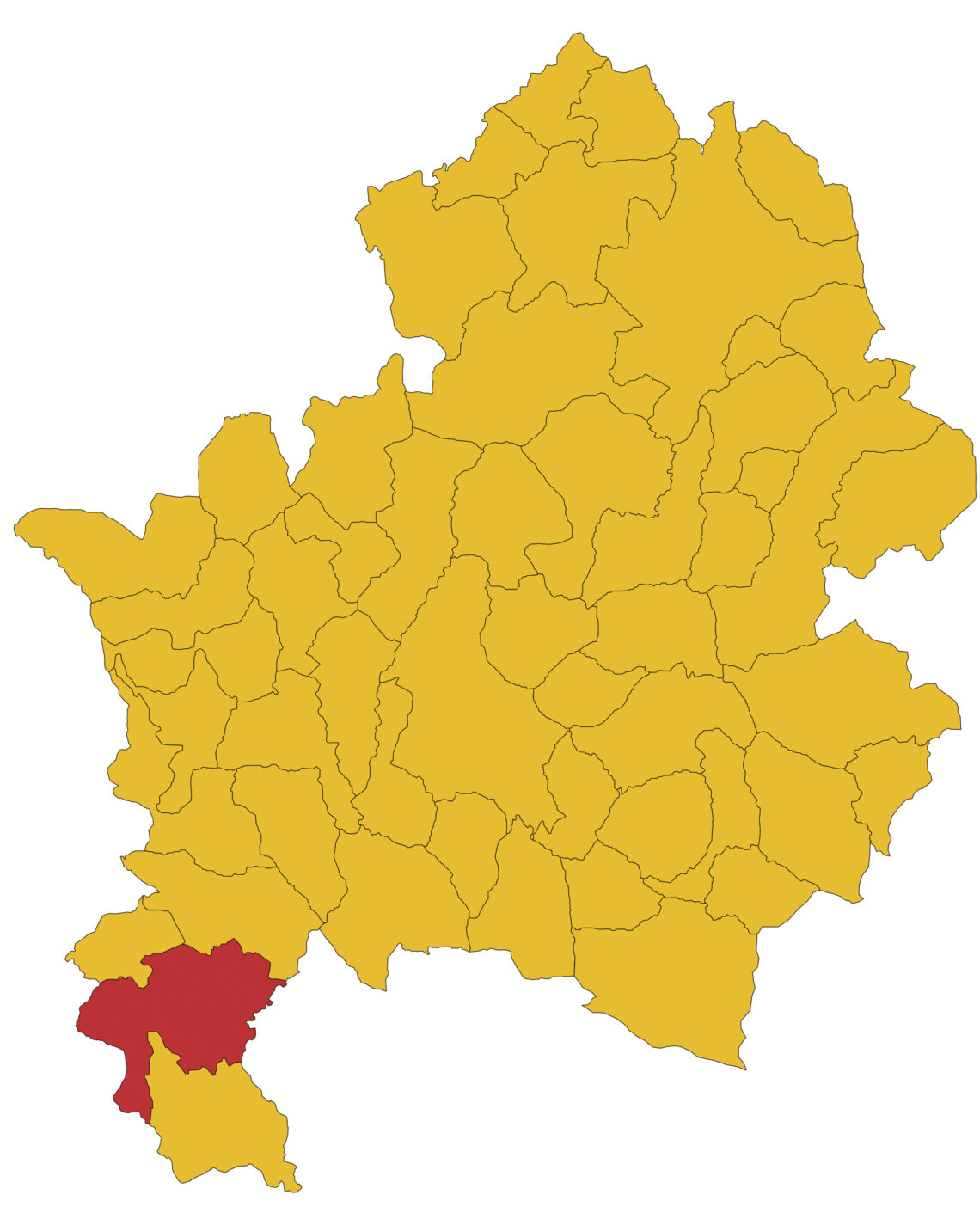

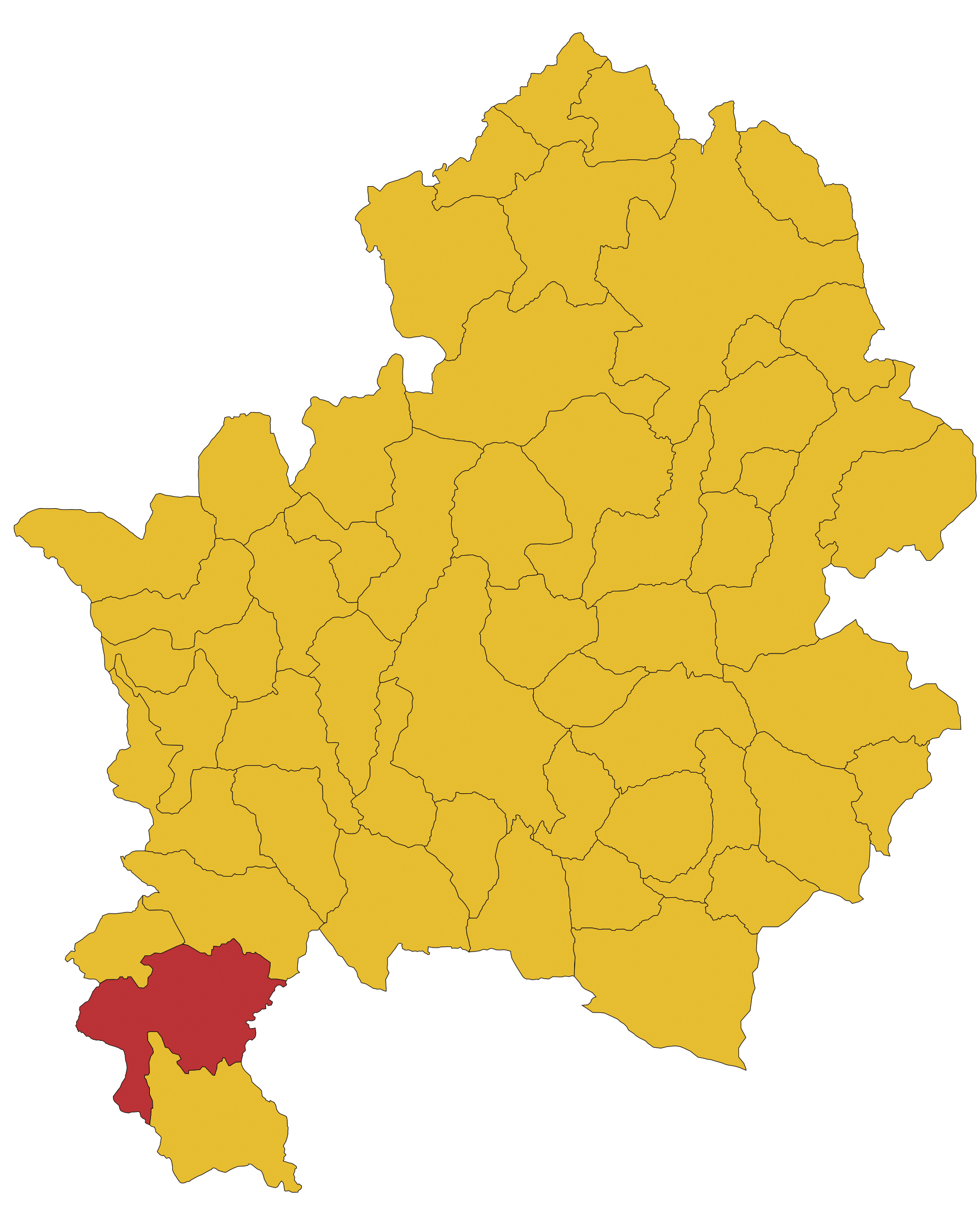

Credit: Vonvikken

Antonio Giordano

Antonio Giordano was born in 1459 in the city of Venafro (population 11,079 in the 2021 Census) in the province of Isernia in the region of what is now Molise. He was tutored at home at the expense of his wealthy parents. Antonio at the age of 18 attended the University of Siena from which he graduated with a degree in jurisprudence in 1481. He then had a successful private legal practice for seven years before he became a law professor at the University of Sienna in 1488. In November 1493, he was elected at the age of 34 to be appellate judge for the city.

In 1494, the military forces of French King Charles VIII (1470-1498) invaded the northern Italian city-states. Giordano was arrested and forced with other political prisoners to follow the French forces on foot for their entire march to Rome. Upon reaching Rome, Giordano and others were released by a direct order from the king himself. When Giordano returned on horseback to Siena, he became an advisor and then the private secretary to the Lord of Siena, Pandolfo Petrucci (1452-1512). Giordano was later named counselor and then Prime Minister of Siena by Petrucci. About this time, he became known as Antonio da Venafro (Anthony from Venafro).

In October 1502, as Prime Minister, Giordano traveled to Palermo on the island of Sicily to represent Siena at the Diet of Magione, which was a Norman church in the city, to negotiate a mutual defense pact with other Italian city-states against the Papal States. Later, Giordano traveled under the military protection of the mercenary leader, Paolo Orsini (1450-1503), to Imola, a section in the city of Bologna in Emilia-Romagna, to sign a peace treaty between the adherents to the Diet of Magione and Cesare Borgia (1475-1507) who was the mercenary leader for the Papal States. After the death of Lord Petrucci in 1512, Siena came under constant military and political pressure from Pope Leo X. Consequently, Giordano resigned as Prime Minister in 1515 and returned at the age of 56 to live in his native town of Venafro.

After four years of self-imposed exile, he left Venafro and moved to the University of Naples where he became a professor of jurisprudence in the Fall of 1519. Because he was perceived as neutral by the Neapolitan king, he was appointed to be a member of the Consiglio Collaterale (Collateral Council) which was responsible for judging cases concerning political matters, as opposed to legal matters. He continued in this post until his death there in Naples in 1530 at the age of 71. He never married.

Giordano was a well-respected statesman. He was highly regarded by contemporary historians, such as Francesco Guicciardini (1483-1540) and Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527). For example, in chapter 22, where private counselors are discussed in Il Principe (The Prince), written by Machiavelli about 1513 and published posthumously in 1532, Giordano is described as “an excellent minister”.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_de_Venafro

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venafro#People

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_VIII_of_France

- https://prabook.com/web/pandolfo.petrucci

- https://www.wondersofsicily.com/palermo-magione.htm

- https//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paolo_Orsini_(condottiero,_born_1450)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imola

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesare_Borgia

- http://forhistiur.net/2016-09-freda/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francesco_Guicciardini

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccolò_Machiavelli

Amico Santabarbara

Amico Santabarbara was born about 1490 in the city of Venafro in the province of Isernia in the region of what is now Molise. Because he was not the eldest son, he would not inherit the family estate. Since his family was prestigious and wealthy, Santabarbara decided, after he completed his education at 18, to fund a mercenary force and embrace a military career. He soon married and had a son Lucio who later accompanied Amico on his military exploits. When Santabarbara began his adventures, he became known as Amico da Venafro (Friend from Venafro).

Nothing is known about his engagements until 1525 when he became allied with another mercenary leader, Lodovico de’ Medici (1498-1526), also known as Giovanni delle Bande Nere (John of the Black Bands). Initially, Amico was a division leader, but he soon became Lodovico’s chief assistant. After Lodovico was killed during the siege of the city of Mantua in the region of Lombardy on November 30, 1526, Amico took his forces to Florence where he was hired with three other mercenary leaders by Zanobi Bartolini Salimbeni (1485-1533), one of the ten magistrates ruling the city, to help defend it against the army of King Carlos V of Spain.

In August 1529, Amico defended the town of Cortona in the province of Arezzo in the region of Tuscany against the Spanish, along with another mercenary leader, Pasquino Corso (c.1496-1532). However, during the next month, he abandoned Cortona without confronting the Spanish further because of an epidemic which had hit the infantry under his command. A month later, he went to guard Florence, flanking the forces of another mercenary leader, Marzio Orsini (c.1464-1529), on the hill of Giramonte outside the city. Near the town of Barduccio, he drove away the infantry forces under the Spanish-allied mercenary, Piermaria dei Rossi. Amico and his men then entered Florence where he was made one of four mercenary captains under Malatesta Baglioni (1491-1531) engaged to defend the four city walls against the Spanish siege.

In March 1530, during the fighting, he was wounded in the arm by a shot from a Spanish harquebus which was a heavy, portable rifle-like gun in which powder was ignited by a match. He was also scalded by the burst of a small barrel of gun powder. Later, another mercenary leader, Stefano Colonna (c.1500-1548), ordered the wounded Amico to tell his men to take certain action, but Amico ignored his order. Colonna was offended and vowed revenge against Amico. So, on May 5, 1530, alone and unarmed, outside the Church of Saint Francis, Amico was attacked by a group of ruffians hired by Colonna and died from 27 knife wounds. Amico was 40 years old.

Sources:

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amico_da_Venafro

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venafro

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_delle_Bande_Nere

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantua

- https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/zanobi-bartolini-salimbeni

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cortona

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasquino_Corso

- https://www.geni.com/people/Marzio-Orsini

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malatesta_IV_Baglioni

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stefano_IV_Colonna

Leopoldo Pilla

Leopoldo Pilla was born in the city of Venafro in the province of Isernia in the region of what is now Molise on October 20, 1805. His parents were Nicola Pilla, a doctor and scholar, and Nicola’s second wife, Anna Macchia, who died when Leopoldo was 13. After his father married again, Leopoldo was sent to Naples to live with a family friend. There Leopoldo studied in the private school of Basilio Puoti (1782-1847) who was a noted literary critic, lexicographer, and grammarian. After graduating from Puoti’s school, Leopoldo entered the University of Naples at 16 to specialize in veterinary medicine. After graduation and qualification as a veterinarian in 1825, he continued at the university to study general medicine and became a doctor in 1829.

His professional career began in the employ of the Bourbon government after he graduated. In 1831, he was sent to Vienna, Austria, to study cholera. There he worked in a military hospital and began to take classes in geology and mineralogy. In 1841, Pilla was appointed professor in charge of geology and mineralogy at his alma mater. After a year, Pilla was hired to teach the same subjects at the University of Pisa. He then began to publish articles in French technical journals about various topics in his two chosen fields. In 1847, he published his opus magnum, the two-volume Trattato di Geologia (Treatise of Geology), for which Pilla is primarily remembered.

When Austria invaded northern Italy in early 1848, Pilla enlisted in the Tuscan University Volunteers and became a captain. After training, his unit was sent to Campo delle Grazie (Field of the Graces) near the municipality of Curtatone in the province of Mantua in the region of Lombardia to secure the river front. On May 29, 1848, Pilla and the students were killed by Austrian machine gun fire at the Osone bridge which they were guarding. Pilla was 42. He never married. A plaque marks the house in which he was born in Venafro. Also, an elementary school is named in his honor in his home city.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leopoldo_Pilla

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venafro

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilio_Puoti

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matteo_Tondi

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curatone

November/December 2022