CIAO BELLOWS: ITALY AND THE RISE OF THE ACCORDION

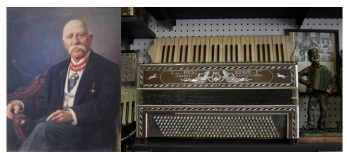

Paolo Soprani and his accordion

The least likely places can have a major impact on history. Take the small Italian town of Castelfidardo, in the province of Ancona in the region of Marche in east-central Italy. Castelfidardo was the site of two events in the 1860s that changed the future of Italy and the world of music.

In 1860, an army from Sardinia defeated the forces of the Papal States as part of the struggles taking place over the future of the Italian peninsula. The Sardinian victory was a significant event in the creation of the unified nation of Italy.

Three years later, a seemingly insignificant encounter also had a major impact on the future of the town, the region and the wider world. For it was in that year that an Austrian man who had been on a pilgrimage to the Catholic shrine in the town of Loreto stopped in nearby Castelfidardo to seek shelter for the night at a farmhouse owned by Antonio and Lucia Soprani. After partaking in a meal, the visitor sat near the fireside and played music on a strange boxlike instrument. One of the Sopranis’ sons, 19-year-old Paolo, became fascinated with the box, which was in fact a version of the instrument the “accordeon” which had been patented in 1829 by an Armenian named Cyrill Demian. Demian’s instrument was primitive, having keys only for the left hand, with the right hand used to push the bellows in and out. Stories vary as to how Paolo obtained a working knowledge of the pilgrim's box, but obtain it he did.

Paolo opened a small workshop in 1864 in his home with assistance from his brothers and began to hand craft an instrument he called an “armoniche,” selling them at fairs and markets, including the pilgrimage site at Loreto with its steady stream of international visitors.

Paolo Soprani and his accordion Soprani achieved enough success to open a factory in the center of Castelfidardo. The popularity of his accordions grew, at first among the local population who incorporated it into their folk music traditions, and then throughout Europe. As Italians emigrated to other nations, especially the United States, Soprani found himself fielding orders from homesick paisani longing for the music of their native land. Paolo moved to bigger headquarters; his workforce grew to about 400, and he eventually developed a production line to manufacture components of his instruments, although the reeds and other delicate parts were still crafted by hand.

Soprani was not the only manufacturer of accordions. In the latter three decades of the nineteenth century, other shops sprung up in Marche and the nearby region of Abruzzo. Sante Crucianelli, Giuseppe Janni, Pasquale Ficosecco, Giovanni Chiusaroli, Raffaele Pistelli, and other craftsmen produced simple diatonic accordions.

Accordion production also had two other major centers, both in northern Italy — Stradella in Lombardy and Vercelli in Piedmont. In 1876, Mariano Dallape began working at Stradella and made important advancements in the development of the piano accordion, which had been invented in 1852. Stradella has also given its name to the standard design and layout of the bass keys on modern accordions.

But no one matched the output of Paolo Soprani’s factory. By 1905, his company was producing 1200 accordions a month, mostly for the Italian market. That was about to change quickly. Industry-wide accordion exports from Italy would rise from 690 in 1906 to an astonishing 14,365 by 1913. Again, emigration played a role, including the movement of talented Italian artisans and musicians to other nations. In addition, Italian-made accordions were considered of higher quality than those made in Germany, France, Russia and Czechoslovakia.

The accordion’s popularity and incorporation into Italian music was so swift that by the end of the 1870s, no less a 9 figure than Giuseppe Verdi put forward a proposal that the instrument be studied in musical conservatories.

The accordion remained popular in the first half of the 20th century. Production hit its first major stumble with the advent of the Great Depression of 1929, which greatly slowed demand, especially from abroad. Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime helped prop up the industry through propaganda, which called the accordion a musical instrument invented in Italy (not quite true) and as being “the pride of our industriousness and the delight of the Italian people” (arguably true), as well as financial support.

The Second World War, however, nearly destroyed the Italian accordion industry. Production went from 51,000 units in 1938 to a low of 500 in 1944. The industry rebounded quickly in the postwar era, however. By 1953, exports had rebounded to 192,058, as the industry employed more than 10,000 people.

And what of the company founded by Paolo Soprani? It merged with the Scandalli company to create a large firm called Farfisa. Other entrepreneurs were entering the business, some from the U.S., and many opened production lines in Castelfidardo. Accordion schools were widespread in Europe and North and South America. Thousands of young students, including this writer, took lessons. Lawrence Welk reigned supreme on Saturday night television.

The boom was not to last. This time it wasn’t war or recession that endangered Italy’s accordion industry. It was changing tastes. During the 1950s and 1960s, a musical style driven more by rhythm than by melody gained traction. The music of Elvis Presley and later the Beatles and Rolling Stones, became the dominant fashion in musical tastes. Rock ‘n Roll was here to stay, and it didn’t have much use for the accordion.

Italy keenly felt the impact. Some of the larger companies were able to adapt their production lines to electric guitars and keyboards. Others, especially smaller, family owned accordion makers, bore the brunt of the downturn. As many as 17 such firms closed in the 1960s.

The accordion has made something of a comeback, as it has moved beyond the staid image of the 1950s. The rise of interest in authentic folk music from many cultures has given the instrument new life and instilled a new appreciation of its musical value. Today, there are sixty accordion companies operating in Italy, with thirty of them in Castelfidardo.

One hundred and fifty-five years after Paolo Soprani met the pious Austrian musician, he would be proud that his hometown remains the beating heart of Italy’s accordion manufacturing and that the instrument is enjoying a renaissance. Musical tastes, however, are notoriously fickle. Perhaps the future of the Italian accordion industry lies in the hope that a worthy successor to Paolo Soprani with the same skill and marketing foresight is working in Castelfidardo today. (Carmine James Spellane is the Secretary of AMHS. After retirement from full-time employment, he resumed accordion lessons after a hiatus of more than 50 years. He wrote this essay as an assignment from his instructor who knew that Carmine would be interested in the history of the instrument given his Italian heritage on his mother’s side.)