One Family’s Italian Immigrant Experience Before and During World War II

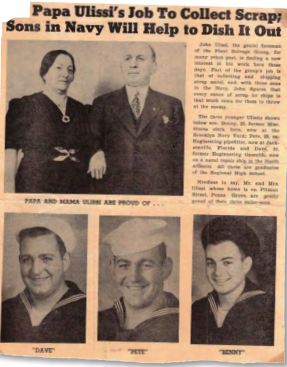

A clipping from a Dupont Company internal newsletter shows Lucia and Giovanni Ulissi and their three sons serving in the Navy. A fourth son, Mark, would later also join the Navy.

My grandmother, Lucia Scorranese was born in 1891, one of seven children living in grinding pover t y on the outskir ts of Valle San Giovanni, a small village of about 1000 people located in the Abruzzi Region of central Italy. [Editor’s note — Abruzzo and Molise were formerly one region know as the Abruzzi.] Lucia never at tended school, could neither read nor write, and spent her teen years doing domestic chores and assisting her father, Paolo, and the family in caring for a small plot of land as tenant farmers. Life was hard. A s a young girl she took a liking to her close neighbor, Giovanni Ulissi, who immigrated to America when Lucia was just 10.

While in America Giovanni was draf ted into the Italian militar y and returned to his native land to fulfill this obligation. Giovanni and Lucia’s feelings for each other blossomed. Lucia quickly accepted Giovanni’s marriage proposal even though it would mean following her spouse to a distant land and likely never again seeing her family and close f riends. Lucia adapted well to her new life in the United States. Her sister, Emilia, lived nearby and just about ever yone on her street spoke the Abruzzi dialect. Lucia never learned English as there was lit tle reason to do so with so many paesani nearby.

Life was good knowing her husband had a steady employment as the manager of a DuPont company salvage yard. Lucia enjoyed things that would have been just a dream in Italy — real shoes f rom a store rather than wooden-sole clogs and dresses made with brand new cloth. No more walking back and for th to the stream with a large urn (conca) on her head to fetch water and wash the family ’s handmade and tat tered clothes. In this new land the dinner plates of Lucia, her husband, and their six children were not hard to fill.

Lucia was grateful. More recent immigrants brought news f rom Italy that the Scorraneses were get ting by despite the worldwide economic depression. Money was tight in both countries but those lef t behind rarely had cash to spend anyhow and her husband told her the new Italian dictator would bring order to Italy and move things forward. Ever y evening Giovanni stayed up to date on the current events listening to news programs on the radio ( bought on credit despite Lucia’s misgivings). Lucia feigned at tention to Giovanni’s comments but in realit y had lit tle interest in these political mat ters focusing instead on providing for her growing family.

Giovanni liked his job and took much pleasure that a dozen or so vallaroli (previous residents of Valle San Giovanni) were working under his tutelage. No English was required, and Giovanni went out of his way to ensure their success. The pace of work accelerated greatly in the late 1930’s. Production increases meant more jobs for the many Italian immigrants who approached him for ‘raccomandazioni’ (recommendations) most helpful in landing a job at DuPont. But Giovanni thought strange the company ’s new polic y that ever y bit of scrap metal be painstakingly inventoried and placed in sealed containers that he had never before seen.

He was shaken when he was visited by his boss’s boss accompanied by an unknown man in a suit — strange garb to be wearing in the salvage yard. He was told to pass on to his workers the need to keep private what they saw and heard while working at the large chemical company. This did not surprise him. What did shock him was the man in the suit’s request to pass on information Giovanni might have about any anarchist or antiwar leanings of the other Italians in the salvage yard or his communit y. ‘Tropp’ ubazz’ ( Too craz y) he thought. Giovanni blamed the new German leader but instinctively realized the increasingly power ful fascisti in Germany and his native Italy were about to convey untold problems to his family and the new countr y he had grown to love so dearly.

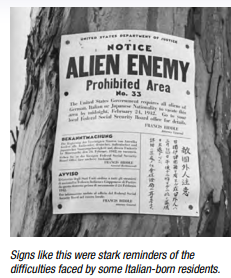

Signs like this were stark reminders of the difficulties faced by some Italian-born residents

How could she be an ‘enemy alien’ after living in New Jersey for 30 years and proudly waving the American flag every 4th of July?

Lucia’s worst nightmares became realit y when Italy entered the Pact of Steel and officially allied itself with a countr y whose ambitions and policies directly opposed those of her adopted homeland. America’s declaration of war against Italy broke Lucia’s hear t. Giovanni had become an American citizen in the 1920’s and, although unlikely to be draf ted at his age, he now had to register for militar y ser vice for the second point in his life — this time in America. Rumors of impending disaster spread quickly as ever yone in Lucia’s neighborhood searched for some small piece of information that might ease their minds.

No one thought it strange that not one Italian in the neighborhood had returned to Italy to suppor t the fascists and fight for their homeland. Even if they had not got ten around to becoming citizens, they were now ‘medigan’ (Americans) and almost without exception, put 100% of their effor ts into crushing the enemies of America. Lucia, too, suppor ted America but saw things differently.

She wanted to crush no one and tried not to think about folly that the men on her street would soon be sent to Italy in mor tal combat against their countr ymen and family members. Things soon went f rom bad to worse. In June, 1940, the U.S. Congress passed the Alien Registration Act, also known as the Smith Act, requiring all aliens to register with the Immigration and Naturalization Ser vice. Lucia complied. With the outbreak of war, on Januar y 14 , 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a proclamation requiring aliens f rom the World War II enemy countries of Italy, Germany and Japan to register with the Depar tment of Justice. Lucia ignored this directive.

“Damn your ancestors!” was all Giovanni could say. Was she really an ‘enemy alien?’ How could this be af ter living in New Jersey for 30 years and proudly waving an American f lag in both hands ever y 4th of July. In her mind she was no one’s enemy. She wanted only for the men to stop fighting and let her mind to her own family. It was not meant to be. Lucia was now allowed to travel f reely only in the communities where she lived or worked. Enemy aliens could travel to/f rom work, religious ser vices, and government agencies but had to carr y newly-issued ID cards at all times.

All other travel required completing a document stating the traveler’s name, address, travel companions, intended destinations, trip purpose, mode of transpor tation and date of return. They were restricted f rom entering areas surrounding for ts, arsenals, airpor ts, electric or power plants, docks, railroad terminals, depots, and other storage facilities. Several large areas in the western United States were totally off limits. Aliens were unable to change residences or jobs without permission of the local U.S. At torney.

All of the information gathered was for warded to the FBI for processing. Under these regulations, Lucia was prohibited f rom owning a radio transmit ter, shor t-wave radio sets, cameras, and firearms. Word on the street grew that Italians would be gathered up and sent to detention camps far f rom their homes and family. ‘Damn!’ was all Lucia could think about the mat ter. Just as these policies came to pass, Lucia’s four sons all voluntarily joined the United States Nav y. She asked each of them to promise to do what they could to avoid going to Italy to fight against their first cousins and Abruzzi comrades. They complied but understood that militar y orders must be obeyed. On November 12, 1942, the U.S. At torney General announced that the restrictions on enemy aliens would no longer per tain to persons of Italian ancestry.

Never theless, Giovanni continued his tireless effor ts to make Lucia a U.S. citizen. These applications were reviewed carefully but with Giovanni working in a war-related industr y and with four enlisted sons, the couple was hopeful that this request would be approved. Late in the year of 1943 , Lucia became a citizen of the United States and she was no longer ‘enemy alien,’ a term she despised and longed never to ut ter again. Just before her naturalization Abruzzi had been “liberated” and was now aligned with the American forces. Her four sons were safe and ‘Dio volente’ (God willing ) would soon return home to work at DuPont with their father.

Only later did she learn that she lost her Italian citizenship on the day of her naturalization. ‘Non menef rec’ (I don’t give a damn) she said to no one in par ticular. From the late 1930’s onward, the United States propaganda machine did its par t in recognizing the effor ts of the Italians in America to suppor t the war. At least three such ar ticles highlighted the life and sacrifices of Lucia Scorranese — an Italian emigrant who kept Valle San Giovanni deep in her hear t while bravely leaving Italy to live and die in Penns Grove, N.J